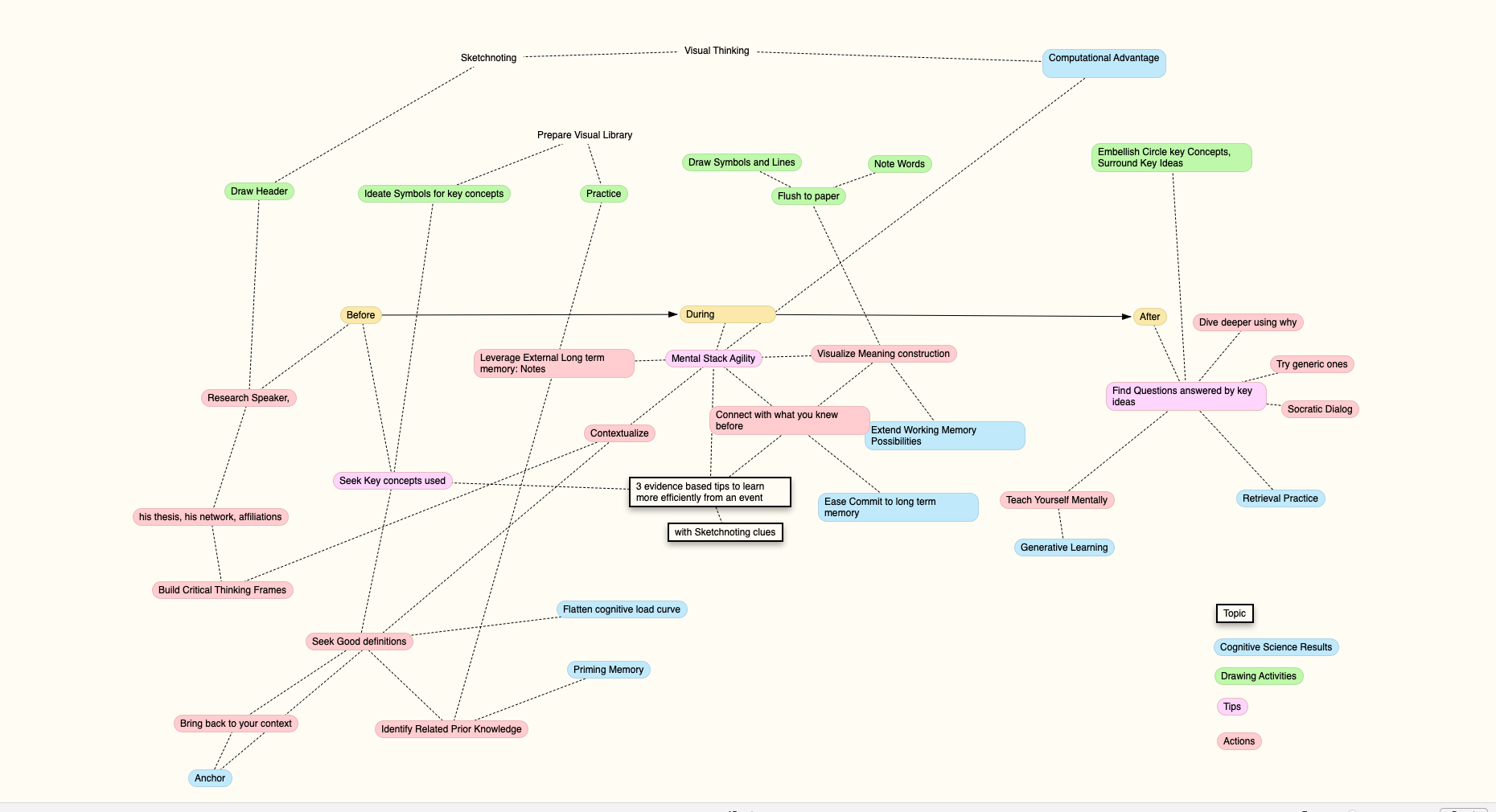

Alternate headlines:

3 Tactics to Learn from Live Events with ease

— with sketchnoting clues

Proven learning practices are not solely for school teachers; we can apply them deliberately in our self-directed journey. Since there is no instructor in charge, you are the one taking care. Let’s grab some pros actionable tips.

You know my love for visual thinking. I added my perspective as a sketchnoter to spice up the list. It will be in italic.

The very first idea is that learning takes time. The more you can spread around the event, the better.

Flatten the curve, they say; let’s apply this general principle to cognitive Load. With some anticipation, it’s easier to keep the cognitive Load under our limit.

Solidifying/cementing learnings is also the reason we need time after.

Cognitive Load: the pressure placed on working memory to assimilate incoming information. You reach overload when you can’t follow despite being focused.

By event, I include courses, webinars, zoom meetups. All are time-boxed experiences with or without replays and slides. Because it’s not under our control, there is a before, an intense moment, and an after. We will see what we can do for each segment.

What to do Before the event

You registered and wait with excitement for the event to start. You know the topic and the speaker’s name. “Can’t wait” they say. You can because you are busy with:

Do a bit of research on the speaker. Grab a picture and a bio.

Identify how you relate to the speaker. Establishing binds will help you get into the talk and memorize who delivered it. That’s going to be a great entry point into your takeaways.

Sketchnoters will take this opportunity to prepare a blank sheet and add the header. A rough portrait of the speaker, key bio elements, possibly illustrated (She’s in Bali? Palm trees, volcanoes, and temples as background).

Search for the topic

What are the key concepts in this field? Identity 10 of them and search for good definitions. Matthew told me earlier that he was quickly lost in a conference yesterday because the speaker was using terms he didn’t know well. If he had done, the day before, a simple search with the speaker’s name and the topic, he would have found them, get a definition. His mind would have elaborate on them unconsciously, and he would join with confidence on those terms and overcome the challenge.

Reword those definitions into bullet-proof ones using your words, your prior knowledge, and your scope. By anchoring the definition to what matters for you, you take ownership. By using your words, you make it easy to memorize them and reuse them on purpose. If you keep someone else definition, like Wikipedia’s, you bring in your mind extra references and jargon that cause more retention difficulties.

How do those concepts relate to your context? My context is adult lifelong learning. In a talk on memory athletes, I will focus on what you and I could apply to keep meaningful knowledge and ignore everything else. That’s my context. Having your context ready will help you frame and anchor new ideas to the situation where you can apply them.

Arm up your critical thinking: A bit of research on alternative views, deviant thinkers, the speaker’s network, recent findings will help you seed some different views and shift point of views during the talk. You broaden your understanding, ask better questions.

Objections:

I don’t have time. Sure, but if you save 25% of the benefit of a 1-hour talk with 15 min preparation, it’s still a good deal. Tell yourself that any commitment to a one-hour event is really a commitment for 1h30. On the bright side, you can choose when you take those 15 minutes: between two tasks, for example. Extra bonus: If you attend several events from the same author, you reuse your work. The other 15 min will be spent after the event.

What to do during the Event

Improve your Mental Stack Agility.

Your working memory is your tool; committing to your long term memory is your goal. How much you can take, chunk, relate, retrieve, and save while keeping a backup in your external memory will condition your hour’s effectiveness. Improving this skill is what I call Mental Stack Agility.

First, manage your focus. Use it like breathing. Breathe in: Focus. Breathe out: release focus, breathe in: focus again. Use the examples and anecdotes shared to release focus. Changes of slides are a signal to focus again. Stories are the easiest thing to commit anyway, its’ an intrinsic skill of Humans, no need for focus: breathe out.

Second: visualize, build a mental picture of what is explained. Oliver Caviogli calls it the “visuospatial sketchpad.” Imagine a pad in your mind and a mental pen to draw on. Visual thinking is a computational advantage. While words quickly overflow our working memory, visual memory can take a lot more. Plus, it forces you to search for visual metaphors, which again can hold a lot more.

If you are a sketchnoter, you will draw some of those pictures in simplified forms using the symbols you prepared.

Third: Relate to prior knowledge. That seems obvious but take it to the next level. Retrieve the best formulation you use and a bit of memory attached to it: when was the last time you used it and for what. This prevents vague recall, the impression you know when, in fact, you only remember the name. If it were a person, it would be remembering the face and two characteristics instead of stopping at the name.

Since you are relating, for the new information, try to find a context or a situation where you could use it. You will make mistakes and errors. It doesn’t matter. Early contextualization will help you focus, stay interested, and build the pathways to retrieve the ideas when you need them.

Last, facilitate committing to long term memory. Ultimately you keep in mind stories, pictures, processes, and concepts. They form small self-sufficient sets (I call them rings, some call them schemas) of ideas that hold firmly together. Classifying incoming information under those types and grabbing them by a handle will help you stack them and organize them very early. Use a memorable handle, like vivid pictures or emotions.

The speaker will not always separate stories, takeaways, or good practices. Do like a left-luggage clerk when you drop your bag: He adds a label to your luggage, even if you had one. Because it follows his scheme of labeling. That’s how he indicates where to store it and make sure it’s yours at pickup time. When a story or an explanation starts, identity it, attach a name deliberately to ease its transfer to long term storage. Like the clerk keeps the bank clear, flush your working memory before the next slide comes in.

PSA for speakers: pause one second before you change slides. It’s not for you; it’s for us.

What to do after the event

Shortly after, the same day:

Fill the gaps

Notes which are taken in urgency always have gaps. It’s time to fix them.

If you have notes and especially visual notes, you can embellish them. It looks very futile, but it increases the reusability of your notes. Fix typos, add frames, colors, a touch of shade.

On textual notes, add links, check the references (A book was mentioned? search for it. A person was mentioned? envision to follow them on Twitter).

The outcome of this work is to identify the key ideas, what you learned really. It’s relative to what you knew already. It can be very few ideas. Please don’t confuse it with a summary. You don’t owe the speaker to collect what you knew already.

Here again, a large difference with students. Students follow a curriculum that assumes they start from a blank slate, and each lesson adds up precisely like tiles. For lifelong learners, learning is more like patches filling gaps and adding extensions.

Seek the questions

Questions are the forgotten child of Personal Knowledge Management. Most people associate them with assessments, exams. Why do you need questions when you can have answers instead? Because questions are the prompts, the entry point inside the memory. The index of your knowledge is your questions, not what you know. The problem is that we have two types of questions: Those issued from the course structure, useless, and those corresponding from situations of use. Focus on the latter.

So for each key idea, find questions to which they are answers. If you can’t find any questions, chances are you don’t need this new knowledge.

Starting the next day:

Teach yourself mentally

Now let’s apply generative learning. This idea is to amplify recollection as deep as possible. As if you were now the teacher in charge of explaining it to others. Always in your context, you don’t need to convey the generality of the original content.

Test yourself using the questions

That’s called retrieval practice. Do it once the next day, once the next week, and again the next month. Don’t focus on the formula but more on the results. Knowledge is better retained by weaving it, using it rather than by forcing it into your mind. Every retrieval practice is an occasion to ask yourself: Why did I learn that? Where can I use it?

If you did all that and you fail to learn, there must be a reason. Search it by auditing your motivation, interest, sources, or process.

If you skipped collecting questions, you could always use generic questions or a Socratic dialog. A monolog, really, because you do both questions and answers. Dive deeper using why several times. Keep track of your gaps.

Conclusion

Now you are equipped with three tactics. When is your next event? Try them and tell me how it went.

This post was written as the final project of Anne Laure’s course from “Collector to Creators”, based on learning from “Research-Informed Teaching in Action”. I combined my experience with the takeaways applied to a constant learner self-directed learning experience.